Buying things is not a shortcut to being interesting

The internet is turning us into uniformed clones and we're too dumb to care

When I was a young teenager, everyone was wearing Joni jeans; the Topshop skinny, high-waisted monstrosities that flattered nobody and flattened the arse of everybody. I had three or four pairs and wore them to death. My personal taste didn’t come into it, I went into Topshop and bought the pair of jeans that I felt might help me to assimilate. When I was fourteen or so, I got a Tumblr account and started listening to Arctic Monkeys, and my idea of cool changed. I wanted to be Alexa Chung, Kate Moss, the girl I followed on Tumblr who posted pictures of cigarettes and American Apparel tennis skirts. I started dressing in the aesthetic now called ‘indie sleaze’, (although my mum always said it was just scruffy) hoping that my ripped tights and oversized charity shop denim would alert other like-minded people to the fact that I was one of them. I wore mom jeans to school on dress down days and slagged off the normies still wearing their Jonis. I was too arrogant and lacking in self-awareness to see that I was the same as them; no better or worse, just buying different tokens in the hope of being admitted to a different club. The problem with this is that an outfit is not a shortcut to an identity, it’s wrapping paper. Adherence to an aesthetic is not a substitute for a personality but if it appears to be so, then what’s the difference?

For teenagers, this kind of behaviour is normal. We’re still figuring out who we are, and we want to be viewed as adults so, we mimic adulthood through our clothes. All of my fashion icons were older than me and living lives that I was envious of, and so I dressed like them in the hope that interesting things would start happening to me. But that’s just teenage insecurity, right? You grow up and stop caring so much. Wrong! The envy remains and the temptation to dress the part instead of figuring out who we are on the inside is still there, but now we have more money and freedom to execute the transformation. We change the goalposts, but the game remains the same (lol, is this a good sports analogy?) We stop buying fishnets and start buying kitchen gadgets or mini Ugg boots or Stanley cups, but these things are just hollow aesthetic signifiers.

So, how does the internet come into it? It validates the false equivalence of aesthetic and identity whilst perpetuating the insecurity that we aren’t good enough and should change. I referenced Tumblr in an earlier paragraph as my doorway into indie sleaze, and that’s what the internet was for me when it comes to style and fashion: a doorway to a different life. Now, with the invention of Tik Tok and its commitment to platforming niche ‘micro-communities’, the internet is less of a door and more of a window. Scrolling Tik-Tok feels like walking down an endless street and peeking in all the windows, viewing aesthetic after aesthetic in quick bursts. The infinite nature of the FYP makes it harder to choose, so we turn into super consumers, jumping from aesthetic to aesthetic on a never-ending quest to finally find the right one. I want that life, no, maybe I want that one. And what happens to the objects from the aesthetics we leave behind? We throw them away.

The production of fashion reflects this carelessness and indecision: trends have become microtrends because the average consumer can’t focus on anything for more than five seconds. In Naomi Klein’s book, No Logo, she writes about the dangers of ‘personal branding’ and companies using an idealised lifestyle to sell us products. At the time of its publication in 1999, it was a warning but at the time of writing it feels more like a conservative but accurate prediction. Idealised marketing has spread into every aspect of our lives, partly because we have influencers now: individuals devoted to displaying their own glamorous lifestyles in order to sell products. And the lines get even blurrier when you consider the fact that many successful influencers go on to create brands and products of their own which they go onto sell to their curated fanbase, effectively eliminating the middleman.

I’m referencing Klein here because No Logo highlights the secret ingredient in the internet identity shortcut cocktail which is (surprise!) capitalism. We are being sold a dream that buying the right things will make us a different person, but these dreams are cheap marketing tricks. This belief has become so pervasive that in the early 2010s #sustainability literally became its own internet trend. A quick search of the hashtag shows videos of creators flogging bamboo toothbrushes and sustainably made leggings, demonstrating the fact that even a movement based on the conservation of resources has products to sell us.

By the time you’re reading this, my thoughts and cultural references will have probably become outdated due to the speed with which conversations move on platforms like Tik Tok. These apps convey a feeling of infinity to make users feel constantly anxious about what they might be missing and as a response, our attention spans are fucked. You’re probably half-reading this essay on your phone or laptop with at least one other tab open. Maybe you’re scrolling through Substack while you ruminate on an online shopping purchase, clicking on and off posts without finishing anything. Because that’s what happens when you buy into the idea that the consumption makes you a different person:

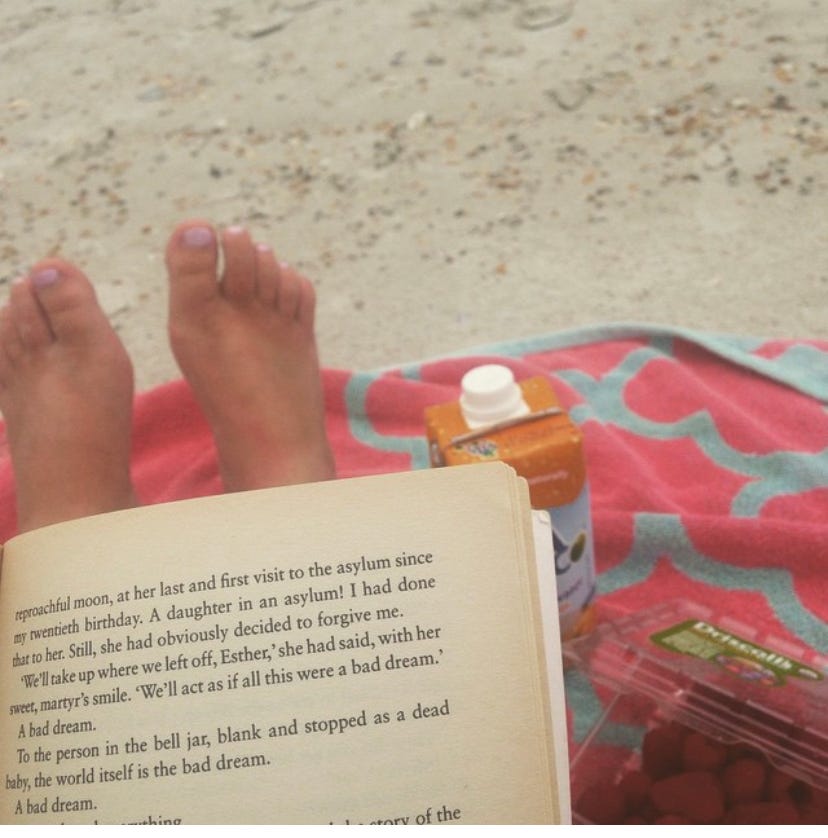

You stop reading, you stop thinking, you scroll and scroll and get stupider and lazier until you are consumer putty in the algorithm’s figurative hands. Let me give you an example: You’re scrolling your social media of choice and you find a post about Dark Academia, a literary marketing term turned subculture that centres a romanticised fascination with classic literature, intellectual pursuits, gothic architecture, and a vintage-y sense of style. This term was popularised (and maybe actually originated?) by the novel, The Secret History by Donna Tarte. So, you like the vibe, you like the pictures of black coffees and old books against autumnal backgrounds, and you think, I want my life to be like this! You google The Secret History which seems like a good place to start and think, oh, 500 pages? Seems long. So, you open a new tab for plaid miniskirts, another one for brown berets, one more for clear-lens glasses. Next day delivery? Click, click, click. All you’ve done is buy things, but you feel different, full of possibility. An imagined life unfolds before you where you are wearing these outfits and drinking black coffees and conversing with chic, intellectuals. You drift off to sleep, soothed, convinced that you have done something positive for your wellbeing. Rinse, repeat.

Does that sound like a good way to live, as a dress up doll for micro trends? Oh sure, you’re convinced that you’re an individualist who has curated a wardrobe of elevated pieces, but that’s a delusion. What if we curated engaging personalities? What if we read a book and then went outside? But wait, here comes the capitalism problem again: most people work jobs that make them feel like shit and do not pay them what they deserve. So we work too much and it makes us feel bad and then we come home and scrolls on our phones and buy things because it’s easier than thinking. And then the cycle resets.

I’m not writing this from a place of superiority, if anything I’m writing this as a reminder to myself. I fall into the identity shortcut trap over and over again, and I’m more susceptible to its charms when I’m tired or feeling low. I buy something at midnight with next day delivery and I fool myself into thinking that the act of purchase was self-care. So, what’s the solution? Destroying the foundation of capitalism that western society balances precariously on top of, obviously. But individually? I think we should slow the fuck down.

When I started writing long-form fiction, I was surprised at how positive it was for my mental health. In a world full of instant gratification, prioritising a creative project that provided me with small pockets of happiness over a long period of time genuinely changed my life. Committing yourself to something that takes a long time to finish and might not bring you anything but the pleasure of creating it is the highest form of self-love I can imagine. And it doesn’t have to be writing, obviously, it can be anything. This kind of work teaches you to be disciplined and it’s also sending a message to yourself that you are worthy of time and investment. It forces you to slow down. The joy that this sort of work brings you might not shine as bright as the instant dopamine of an online purchase, but it burns longer, and it might actually keep you warm.

i absolutely loved your essay and couldn't agree more. i love Naomi Klein (i read this changes everything for uni) and i think she's one of the most forward thinkers we have today. i immediately subscribe to you and can't wait to read more of your work, love from Marseille <3

I read the first paragraph. I fall in love. I subscribe. I'm only a woman. Hello from London 👋